Fiber Optic Biosensor Detects Bacteria In 15 Minutes

By Jof Enriquez,

Follow me on Twitter @jofenriq

Current laboratory tests can take several hours to a few days to detect bacteria, but a new fiber optic sensor can do it in as little as 15-20 minutes.

The biosensor, developed by scientists from the Photonics Research Center at the University of Quebec and the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, consists of an optical fiber bonded with bacteriophages, viruses that latch onto Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. When a beam of light strikes the surface, the presence of E.coli shifts the wavelength, indicating contamination. The sensor could speed up the time it takes to test contaminated food and water, potentially saving lives.

"Using currently available technologies, which are mostly based on amplification of the sample, it takes several hours to days to detect the presence of bacteria. A fast and accurate detection alternative is, therefore, preferable over the existing technology," said Saurabh Mani Tripathi, a physicist at the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, in a news release. "Faster tests for the bacteria could lead to faster treatment of patients, as well as to cheaper and easier environmental monitoring."

Scientists know that temperature changes alter the properties of optical fibers, rendering them less ideal for detecting bacteria accurately. As a result, previous sensors made from these materials have been designed to work at a particular temperature. If it gets too hot or cold, especially outdoors, then readings become inaccurate. Measures to overcome "temperature cross-sensitivity" are promising, but have drawbacks associated with the customized fiber design, increased sensor and detection unit cost, and reduced refractive index (RI) sensitivity due to overlay coating, according to the paper published in Optics Letters.

With their sensor, Tripathi and fellow researchers added an additional optical component to attenuate temperature-induced shifts.

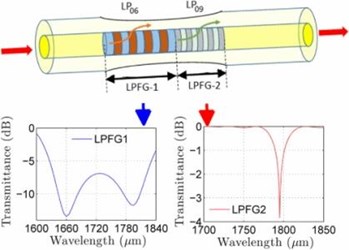

"Surface sensitivity is maximized by operating the long-period fiber grating (LPFG) closest to its turnaround wavelength, and the temperature insensitivity is achieved by selectively exciting a pair of cladding modes with opposite dispersion characteristics," wrote the researchers, who also demonstrated that the device successfully detected E. coli concentration in water over a wide temperature fluctuation of 24°C–40°C.

Temperature insensitive sensors like this can be useful to monitor water reservoirs and in other applications by pathology labs and the food industry. The team is hoping to build portable units that cost a few thousand dollars with the help of Security and Protection International, Inc., a Canadian company.

"Pathogenic bacterial infection is one of the biggest causes of death, and a fast response time is much needed for timely detection and subsequent cure of bacterial infection," Tripathi said. "I'm excited by the very low time [our sensor needs] to accurately detect the presence of E. coli bacteria in water collected from environments at different temperatures."

Other scientists have experimented with lasers to quickly detect and monitor other types of deadly bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans.